Madison's City Budget, Levy Limits, and Bond Reoffering Premiums: More than you wanted to know

Trying to explain what Paul Soglin is talking about

For my next blog post I had planned to write about housing, but the Madison Common Council recently approved the 2024 budget and there was a last minute brouhaha over the debt service and “reoffering premium.” That’s a really technical issue that most folks probably didn’t follow, and normally you wouldn’t need to. However, Paul Soglin has been out banging on about it (and a bunch of other unrelated things) and I’ve seen it picked up a bit - but I still don’t think most folks talking about it other than Paul actually know what it is or how it fits into the larger budget picture, so I am taking a blogging detour to make this post a bit about the budget.

Specifically, I’m going to explain what the dust-up over the vote on paragraph 8 of the 2024 Budget Resolution was all about. That clause reads as follows - which I think you’ll agree isn’t immediately obvious what’s happening here:

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, general debt reserves will be applied to reduce general fund debt service, but the City will not appropriate funds of an equal amount for capital projects. In order to do this, MGO sec. 4.17 requires that this paragraph be approved by a two-thirds vote of the Council.

In order to be able to explain what that’s talking about and why anyone might object, I’m going to have to cover some background information, so this post will be in three parts. Part 1 will give some background on the capital and operating budgets that is important to know, and Part 2 will cover the levy limit, which is the real culprit in this complexity. Finally, with that covered, we’ll get to Part 3 and explain the general debt reserves, reoffering premiums, and hopefully finally pay off the point of this blog post. If I’ve written this post right, by the end of it you’ll know what Soglin is talking about and you can decide for yourself if it’s a problem that needs to be addressed or if it’s just the new normal of how the City needs to balance its budget.

Also, just to be clear, I’m not writing this post just because there were questions during the Common Council budget debate about debt reserves and capital funds when it came time to approve the budget resolution, that’s totally normal. There were questions at last year’s council debate, and the only reason I didn’t need to ask any during those meetings is because, years before I was alder and when I was just a city politics nerd, I had also looked at the rules here and had no idea what was going on, and so I asked city staff for help understanding it. The reason I’m writing about it this year is because it’s taken on a life outside of the budget process and showing up in Facebook groups and Nextdoor and Reddit and neighborhood email lists, and not everyone posting about it really understands it, which turns what could be a good debate into a confusing noisy anger session. So hopefully this will help turn some speculation into grounded facts and help raise the debate.

So, pour yourself a drink and let’s dig in.

Part I: The City of Madison’s Two Budgets

The world does not need another piece explaining capital budgets vs operating budgets, so we’ll try to cover only what’s necessary. One of my PhD advisors used to tell me that ‘teaching is the art of diminishing deception’ in that when you’re explaining something, you start out with a simplified but potentially wrong example, and then once you’ve satisfactorily covered it, you say “well, it’s actually a bit more complicated than that and what we just did isn’t how it really works, here is a new twist” and you add in the new details you need to explain the next part. So that’s what we’ll do in this post, and build up an example budget that has the parts we need to explain the reoffering premium technicalities. If you’d like a more in-depth overview of Madison’s budget, I’d point you to Allison Garfield’s “Madison's property taxes and its financial future, explained” or Alder Field’s summary of the Wisconsin Policy Forum’s review.

For our budget, let’s only concern ourselves with snow plowing. To plow snow, you need to put into your budget the salaries of the people who are going to drive the snowplow and the money to pay for fuel for the snowplows. Oh, and if you don’t already have a snowplow, you have to buy a snowplow.

For companies and governments, it’s best practice to break their budget down into ‘Capital expenses’ and ‘Operating expenses’. The general rule of thumb is things that are used once and then gone are operating expenses, and things that can be used over and over again are capital expenses. In our snow plowing case, the hours we pay to the snow plow driver and the fuel we put into the plows are used up after a plowing run, and the next time it snows we have to start all over again, but we can reuse the snowplow and don’t have to buy it again. So we put the salaries and fuel costs of plowing into the city’s ‘Operating Budget’ and we put the snowplow itself into the City’s ‘Capital Budget’

(As an aside, sometimes it’s hard to decide if things are capital or operating expenses. For example, take the salaries of the planners when they’re writing the City’s Comprehensive Plan. That plan is going to be a ‘thing’ that we’ll pull out and use over and over again for 10 years, in a sense just like the snowplow. In a private business that plan and hence the hours used to create it would absolutely be considered a capital project for tax reasons, so it’s not unreasonable for a government to consider it a capital cost and not an operating cost)

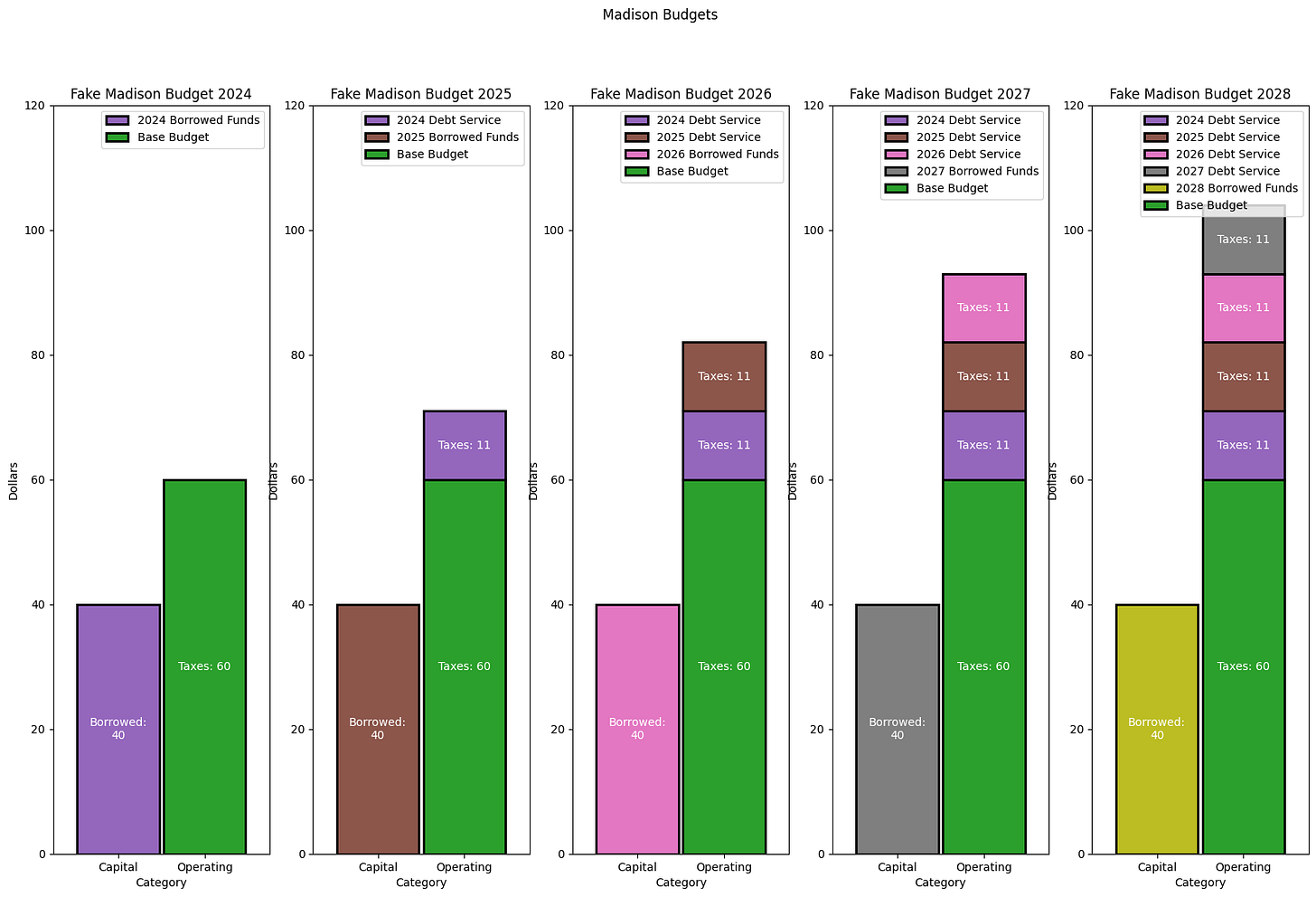

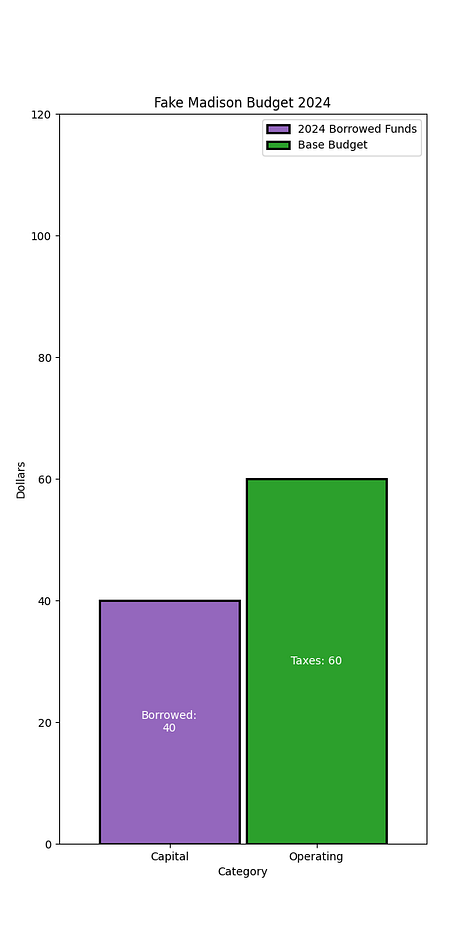

But back to our budget. Let’s pretend that fuel and salaries for snowplowing cost $60, and a snowplow costs $40. That gives us an overall budget of $100, broken down like this:

Now, what’s common is that for items in the capital budget, the City borrows the money to pay for it rather than spending cash on it. Of course, that means we have to pay it back over the next couple of years, and pay a bit more with interest. Debt service is accounted for in the operating budget, so we get something that looks like this:

(Individual images, because the image above will be hard to read on mobile otherwise:)

But of course, maybe we need to buy a snowplow a year to replace old ones, so our budget looks more like this:

(individual images:)

And finally, because we’ve probably bought snowplows in the past, our budget actually probably looks like this, with old debt service rolling off every year and new debt service coming into the budget:

(individual images:)

At this point you’re probably wondering “if every year we’re spending about as much or maybe even a bit more in debt service in any given year as we’re borrowing, why don’t we just stop borrowing money and instead buy things directly and save on the interest?” That’s actually a great question, and in fact some levels of government do that - the State government often just pays for some of its projects out of that year’s taxes and doesn’t borrow for them. The City sometimes does that too - for some things in the Capital budget, the City funds it with a ‘direct appropriation to capital’. For example, the 2024 budget funds new books for the library as a ‘direct appropriation to capital.’

We’ll come back to ‘direct appropriation to capital’ in part III - because that’s at the heart of the budget resolution.

The key takeaway from this section is that in our City simplified budget, in any given year the money the City uses to pay its bills that year are a combination of borrowed money and tax dollars, and part of the operating budget - using tax dollars - pays back the borrowed money from years past. Again, this is super-simplified and we’re leaving out all sorts of things like federal grants and money the city makes from charging fees to park in the parking ramps, but it’s good enough for this blog post.

Part II: The Levy Limit

Let’s go back to a single year’s budget. In our pretend 2024, we have to take in $104 in taxes: $60 to the base operating budget, to pay for salaries and fuel for snowplows, and $44 on debt service for past snowplow purchases (principal and interest.) The City doesn’t have an income or sales tax, so the main way the City taxes is the property tax. The property tax is a little weird - unlike an income tax where the IRS says “Pay us 24% of your income”, when the City sets its taxes it figures out how much money it needs to take in (in our example, $104) and then “levies” that amount on the entire City. Then that total amount gets split up proportionally on all of the property owners, based on the relative value of their property. So from here on out, when we say ‘the levy’, we mean “the total amount of money the City takes in.”

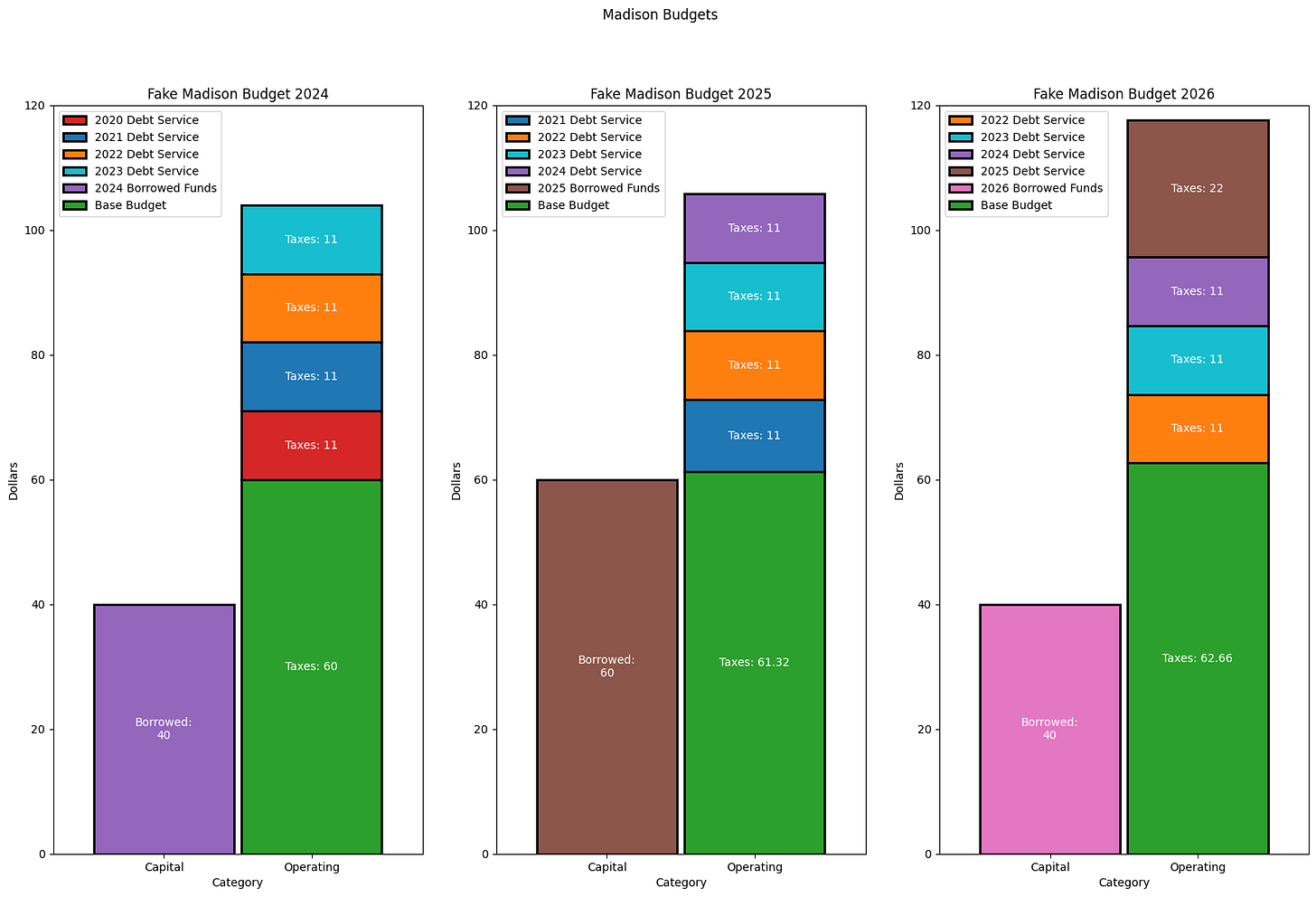

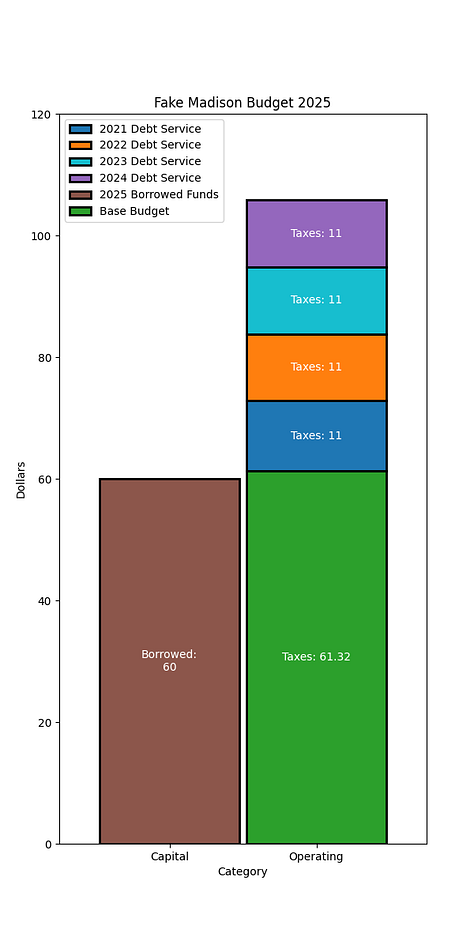

For all of our examples up until now, we’ve also been holding our base operating budget the same at $60 every year, but of course that’s not how the world works. In 2025, it’s likely that fuel will cost more and our snowplow drivers will need a raise, so our base operating budget is going to cost more. Let’s assume our costs have gone up by 5%, which is kind of high but not unusual for the City - the things the City spends money on, like fuel and health insurance, tend to grow faster than the main inflation numbers. Also, let’s assume we need to borrow a bit more in 2025- maybe we need to do some repairs to the snowplow garage. So let’s compare 2024 and 2025:

(individual images: )

So the levy needed to be 104 in 2024 and 107 in 2025 (our increased debt service for the 2025 borrowing doesn’t kick in until 2026 so we don’t have a big rise in debt service - yet). So, we need to raise taxes to cover the new operating costs. Yeah, no one likes taxes to go up but the alternative is to have the snow plow drivers quit, so all the Common Council has to do is vote for an increased levy and we’re done, right?

No, it’s not quite that simple. The State of Wisconsin puts a limit on how much a city can raise its levy in a given year.

Here’s the bonkers part: By default, a city’s levy is only allowed to be what the levy was last year. The default increase for a city’s level is $0.

Did your city’s costs go up because of inflation? Does fuel cost more, or does health insurance cost more? That’s too bad, because the levy limit increase by default is $0.

There are ways for a levy to increase, and the main way is to have ‘Net New Construction’, that is, to have new houses and office buildings and hotels constructed in your city. A city is allowed to raise its levy by the same percentage as there is ‘Net New Construction’. In 2023, there was about $865M worth of new construction, out of a total of about $39B worth of property, so Madison’s Net New Construction rate was 2.2%, which let the City grow its property tax levy, and use that money to pay for new staff and existing staff salary increases and fuel costs and all the other things the City has to pay for.

The City of Monona, by the way, had no net new construction in 2023 - nothing under construction was completed in time - and so its levy limit was not raised and they had to use one-time sources to fund the gap between what they could tax and what costs had gone up.

This whole system is terrible, especially for smaller cities, but Madison is lucky that we should continue to have ‘net new construction’ for quite a long time. However, we would be in real trouble if things stopped getting built in Madison, but that’s a post for another day.

But this post is about bonds and the Madison capital budget, and I’m not just complaining about the levy limit for no reason. This is a weird quirk to the levy limit that is very important.

Debt service does not count against a city’s levy limit.

The first time I learned that I could hardly believe it: the City could borrow as much money as it wanted and turn East Washington Ave into a waterpark with a 4 mile long lazy river, and that had no limit, but there would be a limit on the number of lifeguards we could hire for it. Former Alder Sue Ellingson explained it to me - if there was a limit on how much the city could levy to pay back debt, our interest rate would skyrocket, if anyone would lend to us at all. If there was a limit and the Common Council had to choose between paying the firefighters and paying debt service, it wouldn’t be close. So when Madison sold bonds this year it said:

“The Notes will be general obligations of the City of Madison, Wisconsin (the “City” or “Madison”) for which the City pledges its full faith, credit and power and unlimited taxing authority to levy direct general ad valorem taxes without limit as to rate or amount.”

So back to our diagram - of the $104 of our fake levy, $44 of that was exempt from the levy limit, so the only part that counted against our levy limit was the $60 to $63 increase. That’s more than we’re allowed to have, so we’ll limit it to the 2.2% increase and our maximum operating levy increase was only to $61.32 - if we need to actually get to $63, we’ll have to find other revenue. Let’s also look ahead to 2026, since we’ll pay the increased debt service from 2025 borrowing, and we’ll assume again a 2.2% Net New Construction increase.

(Individual images: )

Notice that the overall fake levy increased by 11.7% in 2026, from $105.32 to $117.66, because of the large increase in debt service, even though our state levy limit was still 2.2%. So that’s an important thing to remember - the debt service doesn’t apply to the levy limit, but it sure the heck applies to the levy, and an 11.7% increase would be a big increase for property owners. The real 2024 budget increased the overall levy by 4.6%

(The levy also isn’t directly what you pay in property taxes, because it’s proportionally spread across based on property values. So if your property went up a lot - relative to everyone elses - your property tax for the year goes up more. The 2024 City budget raised the levy by 4.6% but because the assessed value of my house went up percentage-wise less than that of other folks, my property tax only went up by 2.0%)

The takeaway from this section is you have to be very careful when talking about the levy and percentage increases from year over year, and that the levy limit and the actual levy are different numbers. The number that city property tax payers are directly affected by is the overall levy, but things like city staff pay has to fit in the levy limit.

Part III: The Budget Resolution, Bonds, and ‘Reoffering Premium’

We now have everything we need to get to the original motivation of this blog post - why is there a separate vote on one clause of the budget resolution. The actual budget resolution isn’t that important - it’s mostly a formality to bring everything into one place and to check off some state requirements.

A big part of what the resolution does, however, is give part of the go-ahead to actually borrow the money that will be needed to fund the budget. The City borrows money a bit differently than how you borrow money to buy a car or a house, though it’s not all that different. Instead of going to a single bank and saying “we would like a loan” the City sells bonds and multiple investors bid on those bonds. The City hires an underwriter to help sell the bonds, and the underwriter takes a cut. The investors who make the best offers - i.e. give us the lowest interest rate - get the bonds and pay us for something close to the principal of the bond up front, and then the City makes payments on those bonds for the life of the bond, like a regular loan.

That’s a super-simplified version of the story and isn’t quite how it works, but it’s a good enough story to build on.

There is a quirk in the municipal bond market in that many bond purchasers don’t want to give us the lowest possible interest rate, and so there is a little financial sleight of hand played: investors would rather get a bond that had a slightly higher interest rate, and they’re willing to pay us a bit more up-front to get it. In effect, investors are paying the City the principal and a little bit on top of that principal more to get a “premium” bond that has a higher interest rate.

Now, municipal governments don’t really like this and would generally prefer not to have to sell bonds as ‘premium’ bonds, but the trend in the bond market has been that some investors will only buy premium bonds - it’s easier for investors to resell the premium bonds so they prefer to hold them. So if a city tries to limit how much of a premium they’re willing to sell at, they might find that they have fewer buyers and don’t get as good of a price, so cities are sort of stuck with the practice.

This extra money we get from the investors to sell them a bond as a ‘premium’ bond is called the ‘reoffering premium’, and it can actually be substantial. In 2023, the City sold $116.3M worth of bonds and got $7.8M of reoffering premium.

So maybe you’re thinking all of this controversy is ‘what should the City do with its $7.8M of reoffering premium’, and it kind of is, but it’s not nearly that direct.

By state law, that $7.8M of reoffering premium has to go to pay debt service. So, it would seem easy come, easy go, what are we even still talking about?

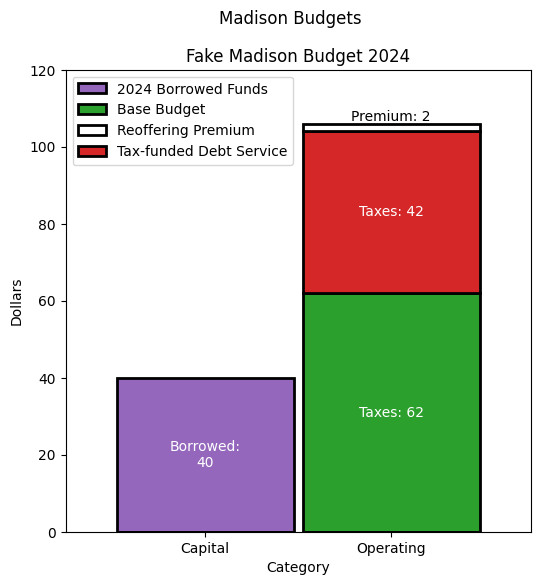

Let’s go back to our fake budget. $44 of that was debt service so it didn’t count against our levy limit, so we can levy the full $104.

Let’s also pretend that for our $40 in borrowing, we got some reoffering premium. Let’s pretend that we got $2 in reoffering premium. That $2 hasn’t shown up on our graph before, let’s change the graph to put the extra $2 in the ‘Operating’’ category. By state law, we have to use that $2 for debt service - so in effect, that $44 of debt service is really only $42.

OK, finally the actual punchline: The way the levy is calculated, the city can still levy the $44, even though it only needs $42 to pay the debt service. Put another way, the reoffering premium ‘generated additional levy capacity’. So we can still levy $104, but we only need $42 for debt service, which means we can have $62 rather than $60 for other parts of our operating budget.

(And it kind of has to work this way, because we won’t know what the reoffering premium amounts are going to be until late in the process, after the state has already calculated the limits for each city.)

You might ask “why don’t we just borrow less and use the expected reoffering premium to cover some of what we were going to use the bond principal for?’ And the answer is you can’t, because by state law the reoffering premium has to go to debt service, and can’t directly be used to offset borrowing. So we couldn’t say try to borrow 95% of what a snowplow cost and count on getting 5% back in a reoffering premium and paying for an entire snowplow - in that case, that 5% has to go to debt service from past years and not the current year’s snowplow.

But we can try to find a way to borrow less and still comply with state law, and that’s what Madison General Ordinance 4.17 and the special clause in the debt resolution are all about.

The City can’t use the reoffering premium directly on capital projects, but it can use an equivalent amount of money from the levy and spend it on capital projects. That’s a ‘direct appropriation to capital’. So the City is still levying $104, still gets $2 in reoffering premium that it’s using for debt service, but now is using $2 of its non-debt-service levy to pay for some capital costs instead of borrowing everything for it. Importantly, that $2 of non-debt-service levy applies against the levy limit, so that’s $2 that can’t be used for salaries or fuel or other operating costs.

In 2012, MGO 4.17 was passed and required this sort of ‘direct appropriation of capital’ be done. (People who remember their history will note this was early in Soglin’s 3rd stint in office.)

In any year when general debt reserves are applied to reduce general fund debt service, an amount at least equal to the general debt reserves applied must be directly appropriated from the general fund for capital projects, unless the Common Council, by a separate vote of two-thirds (⅔) of all members during approval of the budget, votes to do otherwise.

The ordinance and budget resolution text that invokes it is a bit confusing because you sort of feel like you get lost in the double negatives. We’ll break the ordinance down real quick. The first part of the ordinance says ‘In any year when general debt reserves are applied to reduce general fund debt service,’ -- now, ‘general debt reserves’ is just the name of the fund that holds the reoffering premium dollars, so nothing special there. And the ordinance is weird because by state law you have to use the general debt reserves to reduce general fund debt service, so the ‘In any year’ bit is kind of silly, since it’s true every year. So we can just sort of ignore the first part since it’s always true.

If you just ignore the first part of 4.17 because it doesn’t matter, the second part is much more straightforward: ‘an amount at least equal to the general debt reserves applied must be directly appropriated from the general fund for capital projects, unless the Common Council, by a separate vote of two-thirds (⅔) of all members during approval of the budget, votes to do otherwise.’

So this is easy to explain: whatever money the City gets for reoffering premiums (which had to go to debt service) the same amount has to be spent from the levy on the capital budget, unless the Common Council decides not to do that.

And there’s good reason to decide not to take the money from the levy (that’s subject to the levy limit) and use it on capital projects that we could borrow for, and use that money on operating costs, which we can’t borrow for. To be clear, we’re not borrowing to pay for the snowplow driver’s salaries, but if our choice is borrow the full amount of the snowplow and pay the snowplow driver’s full salary and have more debt in the future, or borrow a bit less than the snowplow’s full cost and pay the snowplow driver less but have less debt in the future, which would you choose?

In the 2024 budget, the Common Council went part way: The City got $7.8M in reoffering premium, all of which went to debt service but which also generated an extra 7.8M in levy capacity. The Council used $1.2M of that levy capacity as direct appropriation to capital, and voted by more than the 2/3rds majority to set aside MGO 4.17 and used the remaining $6.6M of levy capacity to fund other priorities in the operating budget rather than funding more capital projects out of the levy.

Part IV So is this good or bad?

One of Soglin’s central claims is that the City is using borrowed funds in the operating budget. I hope that you’ve seen how, depending on your perspective, you can argue that Soglin’s claim is not true and the City is not using borrowed money to fund the operating budget, or how you could argue that Soglin’s claim is true and the City is using borrowed money in the operating budget.

Certainly a very strict reading of the Excel sheets that document the budget and bond term sheets would show that it is not true and the City is not using borrowed money in the operating budget: all of the borrowed money from the bond sales are going to capital projects, none of it is going to things that are clearly only operational. This is not up for debate and Soglin would agree with that.

The reoffering premium is also not going to the operating budget. You can see the money get deposited into the debt service account and then be taken out of the debt service account and applied to debt service. Again this is not up for debate.

The ‘generated levy capacity’ that the reoffering premium provided is just tax dollars, and is not borrowed money. You can’t really track levy dollars like you can the reoffering premium, so it’s hard to say exactly where this extra is being used: is it helping to fund the increase in police salaries? Is it being used to fund the new Equal Opportunity Investigator the Department of Civil rights added for 2024? Is it being used to pay for fuel for snowplows? Yes to all of that.

So to really narrow where Soglin’s claims are valid we get down to two places.

First, one good thing about the levy is that it’s generally stable and we know that next year’s levy will be at least this year’s levy, so when we make things like salary commitments we know the money will be there. And strictly speaking, we don’t know if we’re going to get any reoffering premium next year, so that extra levy capacity that we’re using this year might not show up next year. So in a sense the reoffering premium is a one-time fund, and it is dangerous to use one-time funds for ongoing expenses, unless you’re ready to cut those expenses. So maybe it’d be better to have a separate budget fund of ‘one-time operational expenses’ and explicitly use it for things like capacity building grants in the community or special events in parks. In a sense, that’s what the ‘direct appropriation to capital’ that was used to historically account for the reoffering premium levy capacity: you can go back to past budgets and see that we didn’t use that levy capacity for street reconstruction, we’ve used it for in the past for ‘MarketReady Program’ grants in Economic Development. Now we borrow for the money to support those grants.

We are scheduled to borrow less in future budget years, which could lead to less reoffering premium, so counting on using that generated levy capacity to pay for salaries could be a challenge.

The second place where Soglin’s claims can be true, and where you can argue his point with a straight face, is to make a slightly more subtle version of his argument. It’s not that the City is using borrowed money to fund the operating budget, it’s that the City is spending more in the operating budget because the City is borrowing more in the capital budget. That’s kind of a mouthful so you can kind of see why it’s faster, if less precise, to say ‘the City is using borrowed dollars to fund the operating budget’

It’s not that we could get lower interest rates on our borrowing if we borrowed less, we’re stuck with the higher premium rates on whatever we borrowed, it’s that if we just paid for things directly we would borrow less and have less to repay in the future. It wouldn’t help us with the levy limit in any given year but it would keep taxes on Madisonians down, which is not a bad goal.

But that gets back to a fundamental policy goal that all governments, companies, and individuals face: is it better to borrow and get something sooner, or to save up and wait?

Let’s go back to our hypothetical budget, and pretend that we didn’t quite have the money for a snowplow this year but if we saved our money we’d have enough for one next year. So rather than borrowing this year for the snowplow, let’s wait a year and then pay for it outright and not have to pay interest. That might mean we have one winter where in our fake Madison we don’t plow the snow, so sometimes our residents are stuck at home for a few days after a snowstorm. So the question becomes is it worth it to borrow the money for a snowplow a year earlier, so our residents can get out and go to work, do business, and enjoy life that winter? Is that increase in happiness and productivity in that winter worth more than the interest we’d have to pay to borrow to get the snowplow a year early?

This is the fundamental tradeoff that the Common Council has to solve with MGO 4.17. Is it better to keep borrowing down a bit so taxes don’t rise as fast, or is it better to borrow a bit more and keep paying for the services that the City wants to offer while still delivering the same capital projects?

I hope you see why this is a hard question to answer, and how the various state and local laws make the accounting of our funds a bit hard to follow, and how pithy arguments on social media don’t nearly capture all of the important details of what’s going to be a very loud, messy, and confused public debate for how we as a City want to address the budget challenges looming ahead.

Thanks to David Schmiedicke, the City of Madison’s finance director, for answering my questions about the City budget before, during, and after my time as alder. Any mistakes in this piece are purely my fault for not expanding on Dave’s answers correctly.